This Travelling Exhibition on the ‘Death of Architecture’ Provokes You to Demand Better Cities and Places

13 architects from around India raise their voices in critique, mourn the dying city and reminisce about forgotten beauty in this first-of-its-kind exhibition.

When I heard that an exhibition called the ‘Death of Architecture’ was coming to Mumbai, I braced myself for an onslaught of provocations. On entering the hall of exhibits, I was greeted by something that looked like a ritual burial ground laid dramatically beside the termite-eaten pages of a book (a history book, I fancy). Needless to say, my expectation was heightened.

Perhaps anyone walking into the exhibition should make a dash first to the very end of the exhibits, where panels by Zameer Basrai and Riyaz Tayyibji beckon the attention of a mind seeking provocation (preferably a headily caffeinated one). Both architects make it plainly known that they are critiquing the works of their contemporaries, right from the outset – something that few architects ever do.

Architects critiquing architecture

Busride Design Studio’s Basrai proclaims the death of ‘local’ architecture. His outspoken panels full of words achieve everything that’s possibly allowable in a space of critique when it comes to taking a dig at oneself and at all other responsible ‘murderers’ in the profession with a kind of tongue-in-cheek humour and honesty that only beckons empathy and, I supposed, veiled admiration for the man. He posits how to win an Aga Khan Award, declares that our extolment of the Palmyra House as the grand examplar of ‘local architecture’ is a sure-fire indicator of the death of architecture. Now, ‘local’ can be ‘local’ anywhere, he laments, as long as it is ‘symbolic’. With its striking clarity and frankness, Basrai’s commentary at the last leg of the exhibition is like a balm to the layman who has navigated the rest of the exhibition – with its predominantly esoteric displays – with utter confusion as to why he is being accused of murdering the profession in quite incoherent terms. Basrai provides some clarity, but decides it is the architects who wield the weapon.

Ahmedabad-based Riyaz Tayyibji’s panels are rendered in a kind of hand-drawn solidity that reminds one of the architecture fraternity’s heydays before SketchUp usurped the imagination. He asks whether we are situated today only in ‘momentary time’. By studying three houses designed by his contemporaries, he ponders on the ephemeral nature of the ‘life’ contained by architecture. Deploying a play of language, he seems to overturn his previous criticisms of a library project, in favour of an objective methodology of critique. Tayyibji’s panels teach one to be comfortable with confusion.

Nostalgia for its own sake

There is a certain kind of death that happens when things are ‘forgotten’. Calling our attention to this is the running theme of ‘nostalgia and beauty’ that tints many of the arguments here. Ahmedabad-based Meghal and Vijay Arya grieve over how engineering elements like pumps and tube-wells have sucked the community-forming possibilities of water features away – which previously, one would see in the step-wells, ghats and kunds of yore. The duo’s striking posters juxtapose the beauty of the historical with the clinical character of the technological, with rows of names of by-gone water features written up like on the walls of memorials dedicated to victims of violence. Any exhibition on the death of architecture surely cannot miss a reference to the quintessential riverfront. Contrasting a blank concrete wall with the layered, expansive gestures of a ghat, the Aryas make a pertinent though subtle point.

Rising from the ruins of architecture is a three-dimensional installation by Ahmedabad-based Rajeev Kathpalia that says little, but manages to stir. In the midst of the exhibition’s dense dose of drawings and text, it serves as a moment of pause. “Life can numb us”, believes Kathpalia, “While sometimes, with the closeness of death, you come sharply alive.” He had this profound realisation one time when his parachute malfunctioned on a skydiving trip, causing him to see “things flashing by” with such intensity, in that imminent proximity to death. One chamber of his installation recreates a ‘dead’ ruin, with sounds of the twitter and gurgling of a place that’s alive with nature; while across from it stands a dense agglomeration of skyscrapers and chawls with the vrooming of cars, abuzz with ‘life’ so to say, but somehow entirely numbing in its effect. It is clear that the dead ruins lend much more to the imagination. It seems there is a consensus of sorts that “nostalgia for its own sake is invaluable” – as Samira Rathod says in her panels.

Ode to the dying city

Shabbir Unwalla is also not one to bandy about the bush, being quick to point to the ‘pre-meditated murder’ hatched by the wielders of by-laws. Having chosen to ‘escape’ this circus around by-laws by setting up his practice in Lonavala a long time ago, Unwalla’s heart still grieves for what has come of Mumbai. Architects were previously at the forefront of designing cities, as architects like to often say; they were not merely in the background having to settle for designing private homes. Unwalla’s posters pay homage to the scenic elevations of the Queen’s Necklace promenade, to the arcades and courtyards and pedestrian-friendly streets of much-loved historic cities, arguing that form for form’s sake is a madness that results in placelessness. One wishes that he had gone a bit further in exploring this theme since his argument could raise quite a few questions leading to action.

The ‘dying city’ is a recurring theme here and Mumbai-based Rupali Gupte’s study is perhaps the most nuanced and insightful. It argues that the amount of ‘blur’ a city has decreases as a city develops “from the slums to the skyscrapers”. ‘Blur’ refers to the dissolved edges of a building that double up as spaces for shops, shop extensions, hawker-shops and window-shops and cupboard-shops and one-foot shops. Through a methodical series of drawings, she celebrates the innovativeness of these make-shift shops and objects that bring life to the streets, while bemoaning the blank street edges that are marked by compound walls and parking lots. Conservation architect Vikas Dilawari’s panels make a similar argument (though I confess I was confused for much of it).

Likewise, it is on the otlas, steps and plinths that the city breathes life, argues Girish Doshi, with his beautiful hand-drawn illustrations of “living houses which feel the need to interact with the street” in Pune. Bijoy Ramachandran sees “the value in messy accretions” in the Halasuru Bazaar in Bangalore. Trying to relinquish the “Modernist baggage” that so burdens architects, he tries to integrate the ‘mess’ into his practice, presenting to us an evocative proposal of a whimsical kit of interventions, which includes a Ferris wheel that serves as a makeshift ticket to the rooftops of houses.

Also in search of this elusive ‘life’ is Pramod Balakrishnan, who travelled to a temple town in Tamil Nadu looking to understand how a town could go from being alive with community places, to being dead in a matter of 5 years. Often, it is when a road cuts through these towns that the death knell is rung, he observes. But who are the people living in these built spaces? Pramod Balakrishnan believes the problem is “that we designers call them ‘users’, not human beings.” This theme of ‘inhabitation’ finds itself repeated across several exhibits. Suparna Bhalla of Delhi interviewed people dwelling in commercial centres like Connaught Place and Nehru Place, to see how their sense of life has changed over the years of development. Much to her surprise, she finds that life sometimes emerges from absence.

Who is the mouthpiece of the profession?

Of the collective of 13 architects who’ve come together to plan this exhibition, some prefer to look at the ‘death’ as an opportunity for life, while some prefer to point out exactly what is causing the death (though a remedy seems far); while still others say they simply enjoy ‘making’ too much to really declare that the profession is dying, while another takes a good-hearted dig at the role we all play in this massacre.

It’s quite evident in landscape architect Aniket Bhagwat’s artful poster of “death by a thousand cuts” that the academic institutions and professional bodies have also left much to his imagination. He believes these are possibly the “mouthpieces of the profession” and need to be called into question. Other than this one panel, however, there is strikingly little focus in the overall exhibition on the role of academic institutions, although there are several academicians amongst this collective of 13. Bhagwat, furthermore, seems to take the occasion to pause and reflect on the entire history of architecture, on scriptures, politics, current events, and come what may, situating architecture in a sea of currents, at the mercy of all. Through these reflections, he seems to hope that a kind of spiritual rebirth will happen, which often follows a ‘death’.

With a title like Death of Architecture, this exhibition is clearly meant to provoke. Yet, the exhibition intermittently rises in provocation and falls, rises again and falls, as if oftentimes afeared of its own bold intentions. As far as exhibitions in the field of architecture go, however, this is undoubtedly one of the first of its kind, most certainly in India at least. While exhibitions before this have usually taken the safer route of chronologically laying out narratives and leaving interpretations up to the viewer’s discretion, Death of Architecture decides that it wants to leave people thinking more critically than they did before entering it – particularly about what role they are playing in this game – and that it has no qualms about ruffling some feathers in the close-knitted community of architects in the country.

But who is all this provocation for, one wonders? If it is for the layman who has the power to demand better spaces, as believes Rathod, then does the exhibition persuade him in coherent terms? Is it for the policy-makers who rule the world of by-laws? In which case, does the exhibition persuade him in his language? While there are enough incredible artworks, video installations and even postcards for the lay public to engage with the topic visually, I am still left wondering. Or is it largely for architects and students, to remind them of what is worth fighting for, of why they are here, to say “hang in there, comrades!” Is it to remind the community of how they have the agency to take ethical stands? As Bhagwat asks, “How many times do you put yourself out there in a selfless manner?” Perhaps the exhibition exists to insist that life and beauty remain not curious arguments in exhibitions, but part of our everyday fight in the field, so that they eventually become part of the daily commute to work, part of the Sunday outing to the riverside. Perhaps the exhibition says, speak up. And that is enough.

So much so that I’ve swapped my usual recourse to courtesy for some Basrai-induced candour in this piece. Far from creating disillusionment about the field, however, Death of Architecture seems to reinforce one’s faith in the things that are ultimately quite fundamental – beauty, community, honesty and the simple act of taking joy in doing things. It is on the latter that Mumbai-based architect Samira Rathod hinges her hopeful premise. With childlike enthusiasm, she combines an assortment of ‘found objects’ from a decrepit house in Gujarat into ‘pokey octopuses’ and ‘geisha’s buns’. Her display seems to entreat viewers to abandon all burdened notions about this imminent ‘death of architecture’, and to simply revel in the ‘joy of making’ for a while – perhaps as a reminder, in rough times, of why they chose to do this work to begin with. A beacon of hope in the midst of a deluge, perhaps?

‘Found objects’ combined in new ways, Samira Rathod (SRDA)

The exhibition was on display at Nehru Science Centre, Mumbai, till March 4. It is opening in Baroda on March 17 and will then head to Hyderabad, Bangalore, Delhi, Chennai, Kochi, Pune, Pondicherry, Kolkata and Ahmedabad. Find out when it will come to your city here.

Photographs by Niharika Sanyal

Yatra Archives

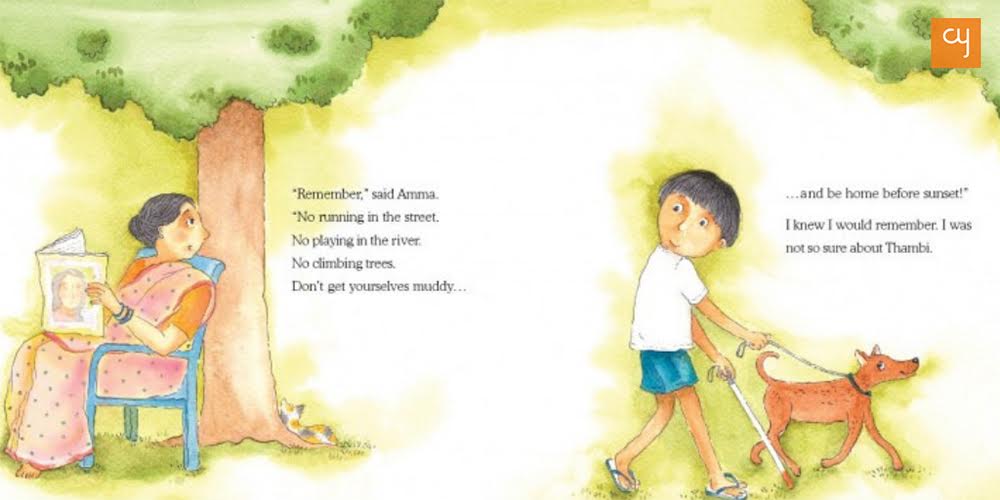

How Tulika Books is creating impact in children’s lives through picture books

Nandini Varma

How Tulika Books is creating impact in children’s lives through picture books

Nandini VarmaAug 21, 2019

A children’s book about a boy who feels like a girl. And about a child brought up by grandfathers. These are some of the stories published by Tulika Books, who have been making children’s picture books since 23 years. Little…

Dalgona Coffee: A worldwide social media trend about home-made café experience

Harshil Shah

Dalgona Coffee: A worldwide social media trend about home-made café experience

Harshil ShahApr 2, 2020

While the lockdown has ignited various trends on social media, one that has received a major global following is #DalgonaCoffee. With thousands of posts on its name, here’s all you need to know about the Dalgona Coffee wave. I first…

Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael and Donatello—Artists or Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles characters?

Harshil Shah

Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael and Donatello—Artists or Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles characters?

Harshil ShahNov 5, 2019

Did you ever wonder where the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles’ characters got their names from? Well, your search is complete. Here is a brief introduction of the artists from whom the creators of TMNT took inspiration. Teenage mutant ninja turtles,…

The call of the mountains: orthopaedic Dr Yatin Desai’s advice on trekking

Himanshu Nainani

The call of the mountains: orthopaedic Dr Yatin Desai’s advice on trekking

Himanshu NainaniMay 24, 2019

In this piece 64 year old Dr Yatin Desai, shares with CY his inspiring story of how to scale towering mountains with utmost ease and how this life adventure activity can shape human character and health. Chances are high that…