Art is born of a convergence of temperament and circumstance. The Iranian director Abbas Kiarostami, who died this Monday (July 4, 2016) at the age of seventy-six was testimony to this. Considered to be one of the most original and influential directors in the history of cinema. Kiarostami was able to work copiously and free-spiritedly within the rigid constraints imposed by the religious and political doctrines of the Iranian regime. Yet he also seemed to thrive on conflict, arising from his over-all sense of resistance to authority and disobedience of norms, which he expressed subtly but decisively in dramatic action and in cinematic form.

This man who tended to shy away, both in his work and in press interviews, from addressing politics or ideology head on, though he never hesitated to decry the censorship and mistreatment of his fellow Iranian filmmakers. He achieved something that few filmmakers ever have: he seemed to create a national identity with his own cinematic style. There’s much to be said about Kiarostami’s place in the now generations long wave of innovative cinema pouring out of his native Iran. Alternatively, you could concentrate on his more recent role as a cosmopolitan filmmaker uninterested in claiming a representatively Iranian identity: Over the course of the last few decades, he shot a documentary about children’s education in Uganda, conducted master classes online from Hong Kong, and contributed to an anthology film with the directors Ermanno Olmi and Ken Loach. Yet, he was the first Iranian filmmaker who expanded the history of cinema not merely in a sociological sense but in an artistic one, and his tenacious, bold, restless originality—an inventive audacity that carried through to his two last features, made outside of Iran—focussed the attention of the world on the Iranian cinema and opened the Iranian cinema to other directors who have followed his path.

The first paradox of Kiarostami’s career is the clash between documentary and dramatic elements, between the observed and the imposed, between the discovered and the determined—and between the closed world of the movie shoot and the total one behind the camera. He worked mainly with non-actors whom he encountered on location, as in his 1987 feature “Where Is the Friend’s Home?,” the story of a schoolboy in the rural village of Koker who travels to another village to give a classmate a notebook, in the process defying parental authority, and other authorities as well. That region was devastated in 1990 by an earthquake; in the 1992 feature “Life and Nothing More,” Kiarostami dramatized his trip to Koker after the disaster to inquire about the movie’s young star, with an actor playing the director. One of the film’s key incidents is an encounter with a newlywed man who married his fiancée the day after the earthquake (they spend their first nights together in the shelter of ruins). Kiarostami followed that film with “Through the Olive Trees,” a story based on the life of the local mason who played the newlywed groom in “Life and Nothing More.” The director is a character, too, and he gets involved in the couple’s relationship. For that matter, the movie opens with an actor addressing the viewer, identifying himself as an actor playing a director who has come to Koker to choose an actress for a film.

Unlike some of his compatriots, he was never jailed by the country’s religious regime, largely because; at least until making the frankly critical Ten in 2002, he found indirect ways of presenting the realities of everyday life in Iran. Before Ten, the first of his feature films to be banned, Kiarostami was sometimes accused of ignoring the concerns of women. It was a choice he had made in part because stories involving child protagonists were easier to get past the censors in a country where women’s unveiled heads, never mind the conflicting ideas roiling inside their skulls, were considered too provocative to be shown onscreen. But late in his career he expressed regret about this omission and began creating female protagonists who were notably—and in the case of films like Certified Copy or Shirin, outstandingly—nuanced and complex.

Like most artists endowed with a supreme, epoch-dominating creativity, Kiarostami couldn’t settle for less—including in his own work—even at the risk of personal misunderstandings and public misconceptions. His last film, “Like Someone in Love,” which he made in his seventies, is a daring new direction in his cinema and in the world of cinema at large. In short, he kept on getting better, which makes his death all the more tragic.

Yatra Archives

How Tulika Books is creating impact in children’s lives through picture books

Nandini Varma

How Tulika Books is creating impact in children’s lives through picture books

Nandini VarmaAug 21, 2019

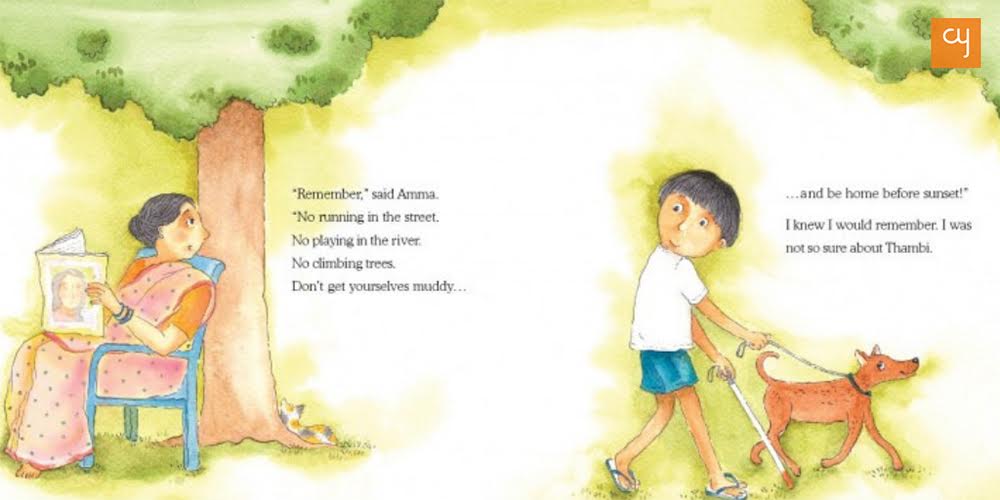

A children’s book about a boy who feels like a girl. And about a child brought up by grandfathers. These are some of the stories published by Tulika Books, who have been making children’s picture books since 23 years. Little…

Dalgona Coffee: A worldwide social media trend about home-made café experience

Harshil Shah

Dalgona Coffee: A worldwide social media trend about home-made café experience

Harshil ShahApr 2, 2020

While the lockdown has ignited various trends on social media, one that has received a major global following is #DalgonaCoffee. With thousands of posts on its name, here’s all you need to know about the Dalgona Coffee wave. I first…

Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael and Donatello—Artists or Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles characters?

Harshil Shah

Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael and Donatello—Artists or Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles characters?

Harshil ShahNov 5, 2019

Did you ever wonder where the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles’ characters got their names from? Well, your search is complete. Here is a brief introduction of the artists from whom the creators of TMNT took inspiration. Teenage mutant ninja turtles,…

The call of the mountains: orthopaedic Dr Yatin Desai’s advice on trekking

Himanshu Nainani

The call of the mountains: orthopaedic Dr Yatin Desai’s advice on trekking

Himanshu NainaniMay 24, 2019

In this piece 64 year old Dr Yatin Desai, shares with CY his inspiring story of how to scale towering mountains with utmost ease and how this life adventure activity can shape human character and health. Chances are high that…