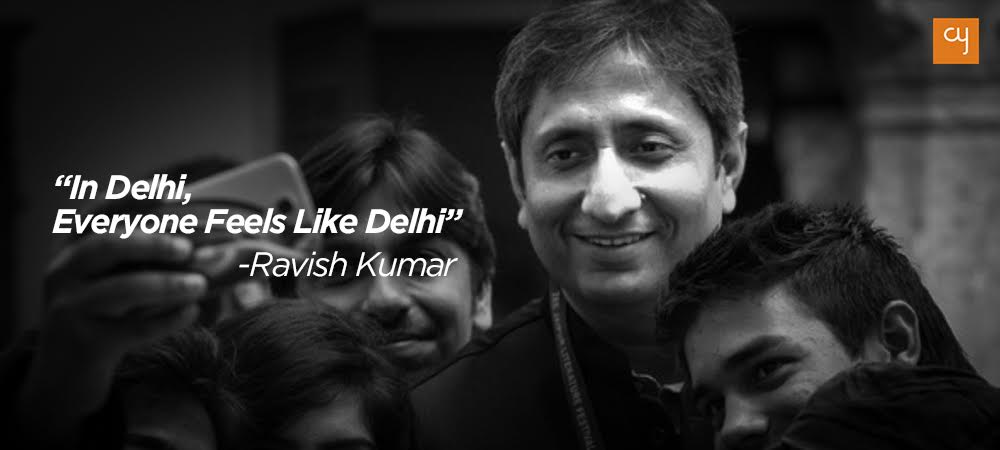

“In Delhi, Everyone Feels Like Delhi”: Ravish Kumar’s book explores love in Delhi

Journalist Ravish Kumar’s book of very short stories‘ Ishq Mein Shahar Hona’ explores the struggle to find a space to love in a city like Delhi.

In my initial days in college, I’d only known Ravish Kumar as the journalist who opened debates that very few had the courage to hold, sometimes from lesser-known areas. This was before I listened to him at the Times Lit Fest held in New Delhi in its first year, 2015. Here, in the grand lawns of the Maidens Hotel, I witnessed for the first time Ravish Kumar the poet, outside of newsroom discussions, writing with a distinct simplicity. As he read beautifully from his book Ishq Mein Shahar Hona, he stood for what he always does, albeit expressing this through a different medium—the politics of love.

In an interview with The Quint, Ravish Kumar introduces his book as one that is made up of “kavita, kahani, qissa”. So, I take the liberty of calling it something like that—a book of poems, stories and episodes—because drawing a conclusion over its genre would perhaps only be an attempt at finding our own familiarity a home. Thus, when he begins to contemplate how a city becomes empty at night, as if everyone has gone elsewhere, leaving it behind all alone—“Raat ko shahar kitna khaali ho jaata hai, na! Lagta hai saare ise akela chhod kahi aur chale gaye”—I’ve already forgotten if the poster to his session said it was about poetry, everyday debates, or simply a reading of his works. Instead, I’m immediately drawn into the quiet beauty of his words and the realness of the conflicts he experiences when he notes—“Gaon mein ghar nahi khota hai lekin shahar mein kho sakta hai”—one can always find home in a village, but one can lose it in a city.

Love and the City

RAVISH KUMAR was born in Motihari, Bihar, in 1974 and completed his high school education in Patna, after which he shifted to Delhi for further studies. Ishq Mein Shahar Hona, a part of the broader trilogy titled “Laprek: Laghu Prem Katha” (short love stories), is dedicated to his wife Nayana Dasgupta, whom he met in Delhi, who is now a history professor at Lady Shri Ram College. In his introduction to the book, he takes us to the moment when he first arrives in the city of Delhi. Moving from a sense of home in his village to the strangeness in the city, he wrestles with several questions, as one often does, on the way to a transformation of perspectives.

From witnessing instances full of light humour and the wonder of an outsider in the city, we also witness his acceptance of the advantages that he begins to see in the city. One of these, he says, is the way one can love here: “Dilli ka ajnabipan romance ka sabse achcha dost hai. Gaon ki tarah yahan mujhe na koi jaanta tha, na pehchaanta hai”—the unfamiliarity of Delhi is what makes it a better friend of romance, as compared to the familiarity that the village brings with it. No one knew me here, no one recognised me.

In his journey, he met many who guided him. He fondly remembers Professor Parthasarathi Gupta, whose lectures on urbanisation during his Master’s days transformed his thinking. He also celebrates his friendship with writers Vineet Kumar and Girindra Nath Jha, who have contributed to the Laprek trilogy with their books Ishq Koi News Nahin and Ishq Mein Maati Sona respectively.

In the background of this city and its locations, as well as in what it comes to stand for, is the overarching metaphor of the book. It is a city found in love and discovered through it. And sometimes, it is so much like ourselves that we become it.

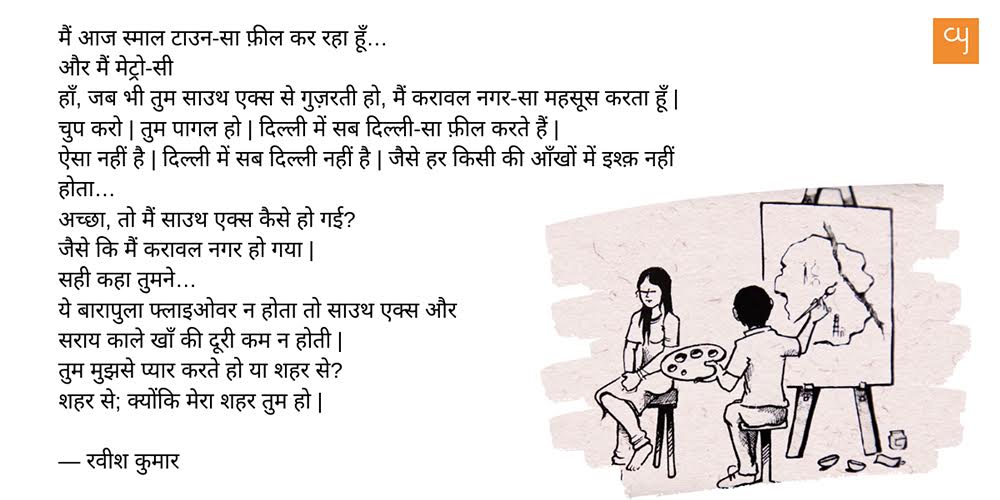

“In Delhi, everyone feels like Delhi

That’s not how it is. Not everyone in Delhi is Delhi”

In bringing his friendship and love for Nayana through dialogues between them in his stories, Kumar also leads us to deeper questions that lie at the heart of the book, that give rise to conflicts in love—like the way that relationships, when brought home to a village that lies far away from transformation in thought, break down in most cases because of the trenchant issues of caste. Therefore, in the stories, one finds undertones of tension and many moments that turn stark.

For instance, in one of them, he draws an analogy between his dreams and the flyovers in the city of Delhi that deceive him: “Tum flyover ki tarah sapne dikhati ho. Pata hi nahi chalta ki dhalaan se uttarte hi sapne jam mein phas jayenge. Medical flyover ki tarah hawa mein udne ke sapne dhaula kuan ki taraf uttarte hi kaafoor ho jaate hai ”—you show me dreams that are like flyovers; one cannot look ahead and see that, as soon as one gets off it, one ends up stuck in a terrible jam. Like the medical flyover, the dream to fly too collapses as it approaches the end, as one proceeds towards Dhaula Kuan (the busy intersection in Delhi).

Ravish Kumar fought the battle of inter-caste marriage himself. Therefore, in portraying love, he doesn’t shy away from writing about the politics that affect it. From running away from policing in the sweets corner where the two lovers first met and which they repeatedly visited, to fighting the extremity of summer under the shade of trees outside India Gate, we travel with him. We find moments of intimacy and delicate beauty that are hidden and often chased by a world that carries binoculars to trace it and then erase it.

Questions of Culture and Language

In an anecdotal piece, Kumar writes about meeting with a momo lady at Lajpat Nagar and falling in love with her. In this interaction lies an observation that Ravish Kumar makes, “Cultures can meet only in the marketplace.” He recalls in this piece (translated by poet Akhil Katyal from Hindi):

“He fell for the girl selling momos in Lajpat Nagar. So far he’d seen the seven-sister states of the North East only on a map. To stroll here every evening had become a habit for him. Secretly, she started giving him one extra piece for every plate of momos. After she smiled once, he began to say, it’s very nice, each time he’d leave. After seeing Shahrukh’s Dil Se, it seemed to him that this one extra momo was paving a new way for love.”

A dichotomy within language and culture becomes a common theme in his stories. In one such story, while discussing the corporates and their giant plans, he writes, “Sector four market ka chauraha tamaam jhoote vaadon ke utarne-chadne ka gawaah raha hai. Hum bhi ek din yahin hoarding mein taang diye jayenge”—the crossing at Sector 4 market witnesses many false promises. We too will, someday, be hung on one of these hoardings.

In another story, meanwhile, he takes us straight into the conversation that takes place between two lovers in the city, as they reach the INA market in search of sea-fish. The fisherman, on looking at the parked Pulsar and helmets in their hands, understands that they are “cookery book” readers, that they may be irregulars to the market and that therefore they may be new to the ways of life here. The irked lover responds in a strange manner by speaking in English, while the narrator wonders what makes her behave so.

The question of language returns in another piece, slightly differently: “What a nice poem—‘sabse khatarnak hota hai hamare sapno ka mar jaana…’ friends colony ke pebble street mein beer peetey waqt usne yeh sawaal uchaal diya—hindi poetry popular kyun nahi hai?” ‘Why isn’t Hindi poetry popular?’—this story begins with a discussion on a poem by the well-known poet Paash, “SabseKhatarnakHota Hai” where the narrator’s lover reflects if it would be any different, had he written those lines in English. He’d have perhaps won the Booker Prize, she says. Although she doesn’t curse him, he starts cursing himself. By taking us to this moment, we are shown the constant struggle of those writing in languages other than English and the lack of recognition of their work.

Ravish Kumar shows us the complexities that lie between a city and the love that blooms or sometimes dies within it. While, in the book, there are heartwarming episodes describing how he listened to Nayana lecture for hours on Mughal architecture, and there are glimpses into the innocent conversations between them, there are also descriptions of violent policing that take place to displace love from the streets of the city. Kumar shows us these complexities while interspersing narrations with dialogues, Hindi language with patches of English, seriousness with breeze-like gentle humour, and love with the fear of separation. Kumar closes the book by reflecting: “Lokpal ki jagah, ek lovepal ban jaye… kitna achcha hoga, tab hum Humayun ke makbare ke maidaan mein ekdoosre ki godh mein sone ka bahana nahi karenge”—if only they could pass a bill for love; how great would it be to love uninhibitedly, without excuses.

***

Listen to Ravish Kumar read from his book in this must-watch video.

Yatra Archives

How Tulika Books is creating impact in children’s lives through picture books

Nandini Varma

How Tulika Books is creating impact in children’s lives through picture books

Nandini VarmaAug 21, 2019

A children’s book about a boy who feels like a girl. And about a child brought up by grandfathers. These are some of the stories published by Tulika Books, who have been making children’s picture books since 23 years. Little…

Dalgona Coffee: A worldwide social media trend about home-made café experience

Harshil Shah

Dalgona Coffee: A worldwide social media trend about home-made café experience

Harshil ShahApr 2, 2020

While the lockdown has ignited various trends on social media, one that has received a major global following is #DalgonaCoffee. With thousands of posts on its name, here’s all you need to know about the Dalgona Coffee wave. I first…

Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael and Donatello—Artists or Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles characters?

Harshil Shah

Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael and Donatello—Artists or Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles characters?

Harshil ShahNov 5, 2019

Did you ever wonder where the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles’ characters got their names from? Well, your search is complete. Here is a brief introduction of the artists from whom the creators of TMNT took inspiration. Teenage mutant ninja turtles,…

The call of the mountains: orthopaedic Dr Yatin Desai’s advice on trekking

Himanshu Nainani

The call of the mountains: orthopaedic Dr Yatin Desai’s advice on trekking

Himanshu NainaniMay 24, 2019

In this piece 64 year old Dr Yatin Desai, shares with CY his inspiring story of how to scale towering mountains with utmost ease and how this life adventure activity can shape human character and health. Chances are high that…